Web Standards - Cookies History & How It works

Information drawn from

A brief history of cookies

HTTP, or the Hypertext Transfer Protocol, is a stateless protocol. According to Wikipedia, its a stateless protocol because it “does not require the HTTP server to retain information or status about each user for the duration of multiple requests.” You can still see this today with simple websites – you type in the URL to the browser, the browser makes a request to a server somewhere, and the server returns the files to render the page and the connection is closed.

Now imagine that you need to sign in to a website to see certain content, like with LinkedIn. The process is largely the same as the one above, but you’re presented with a form to enter in your email address and password.

You enter that information in and your browser sends it to the server. The server checks your login information, and if everything looks good, it sends the data needed to render the page back to your browser.

But if LinkedIn was truly stateless, once you navigate to a different page, the server would not remember that you just signed in. It would ask you to enter in your email address and password again, check them, then send over the data to render the new page.

That would be super frustrating, wouldn’t it? A lot of developers thought so, too, and found different ways to create stateful sessions on the web.

The invention of the HTTP cookie

Lou Montoulli, a developer at Netscape in the early 90s, had a problem – he was developing an online store for another company, MCI, which would store the items in each customer’s cart on its servers. This meant that people had to create an account first, it was slow, and it took up a lot of storage.

MCI requested for all of this data to be stored on each customer’s own computer instead. Also, they wanted everything to work without customers having to sign in first.

To solve this, Lou turned to an idea that was already pretty well known among programmers: the magic cookie.

A magic cookie, or just cookie, is a bit of data that’s passed between two computer programs. They’re “magic” because the data in the cookie is often a random key or token, and is really just meant for the software using it.

Lou took the magic cookie concept and applied it to the online store, and later to browsers as a whole.

Now that you know about their history, let’s take a quick look at how cookies are used to create stateful sessions on the web.

How cookies work

One way to think of cookies is that they’re a bit like the wristbands you get when you visit an amusement park.

For example, when you sign in to a website, it’s like the process of entering an amusement park. First you pay for a ticket, then when you enter the park, the staff checks your ticket and gives you a wristband.

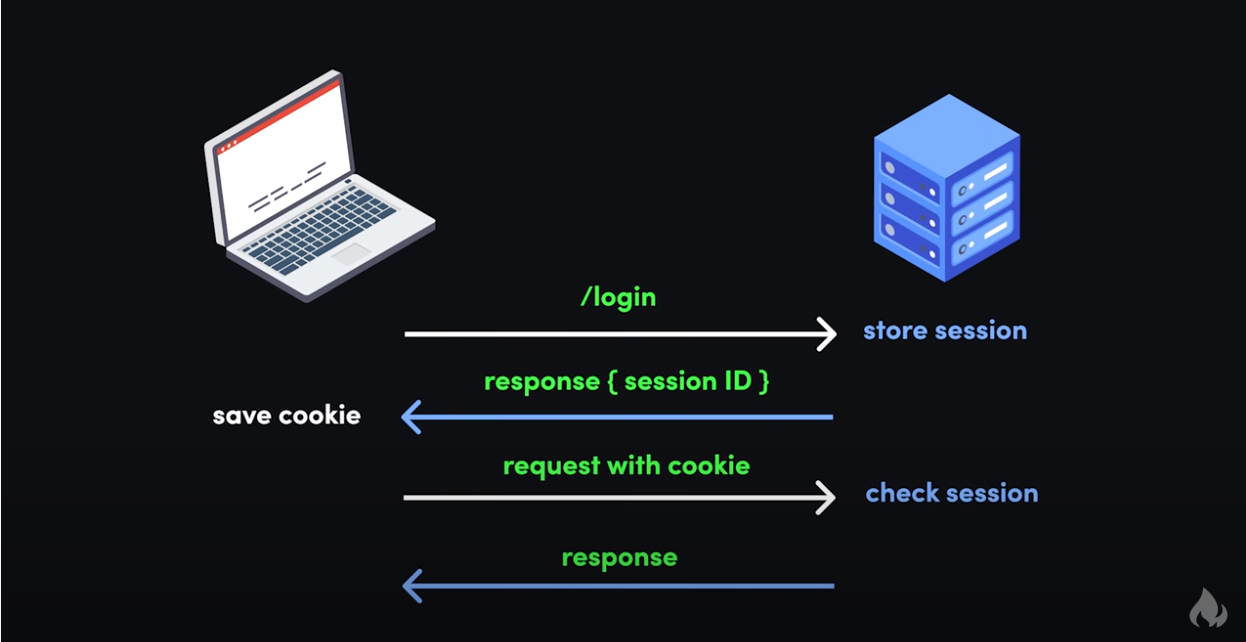

This is like how you sign in:

- the server checks your username and password.

- creates and stores a session

- generates a unique session id

- and sends back a cookie with the session id.

Note that the session id is not your password, but is something completely separate and generated on the fly. Proper password handling and authentication is outside the scope of this article, but you can find some in depth guides here.

While you’re in the amusement park, you can go on any ride by showing your wristband.

Similarly, when you make requests to the website you’re signed in to, your browser sends your cookie with your session id back to the server. The server checks for your session using your session id, then returns data for your request.

Finally, once you leave the amusement park, your wristband no longer works – you can’t use it to get back into the park or go on more rides.

This is like signing out of a website:

- Your browser sends your sign out request to the server with your cookie,

- the server removes your session

- and lets your browser know to remove your session id cookie.

If you want to get back into the amusement park, you’d have to buy another ticket and get another wristband. In other words, if you want to continue using the website, you’d have to sign back in.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Last update on 06 Apr 2022

---