Webpack - Intro to Federated Modules and Micro-frontends

Information drawn from

What are Micro Frontends?

The term Micro Frontends first came up in ThoughtWorks Technology Radar at the end of 2016. It extends the concepts of micro services to the frontend world.

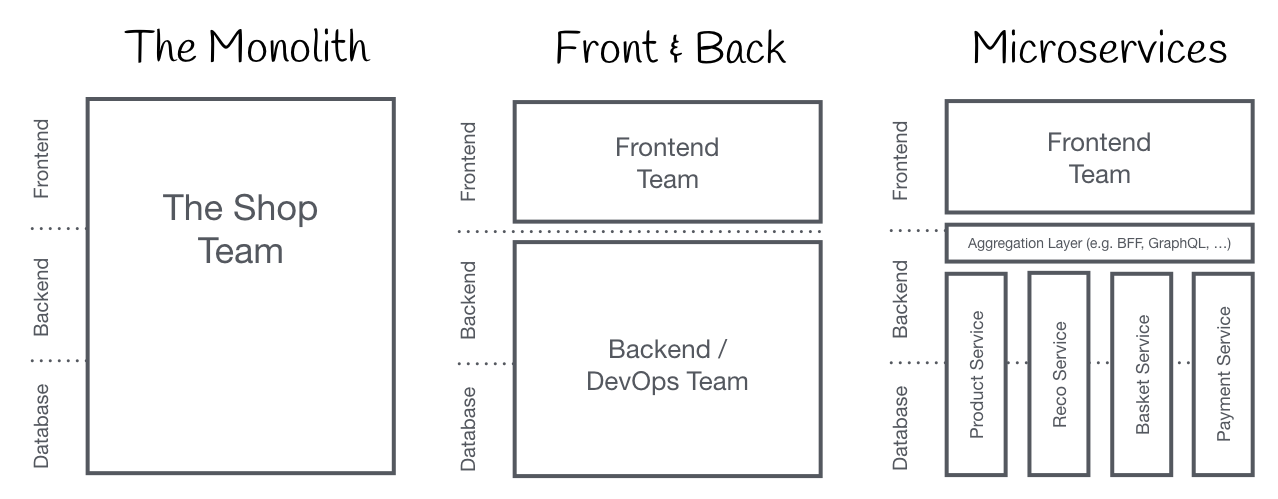

The current trend is to build a feature-rich and powerful browser application, aka single page app, which sits on top of a micro service architecture. Over time the frontend layer, often developed by a separate team, grows and gets more difficult to maintain. That’s what we call a Frontend Monolith.

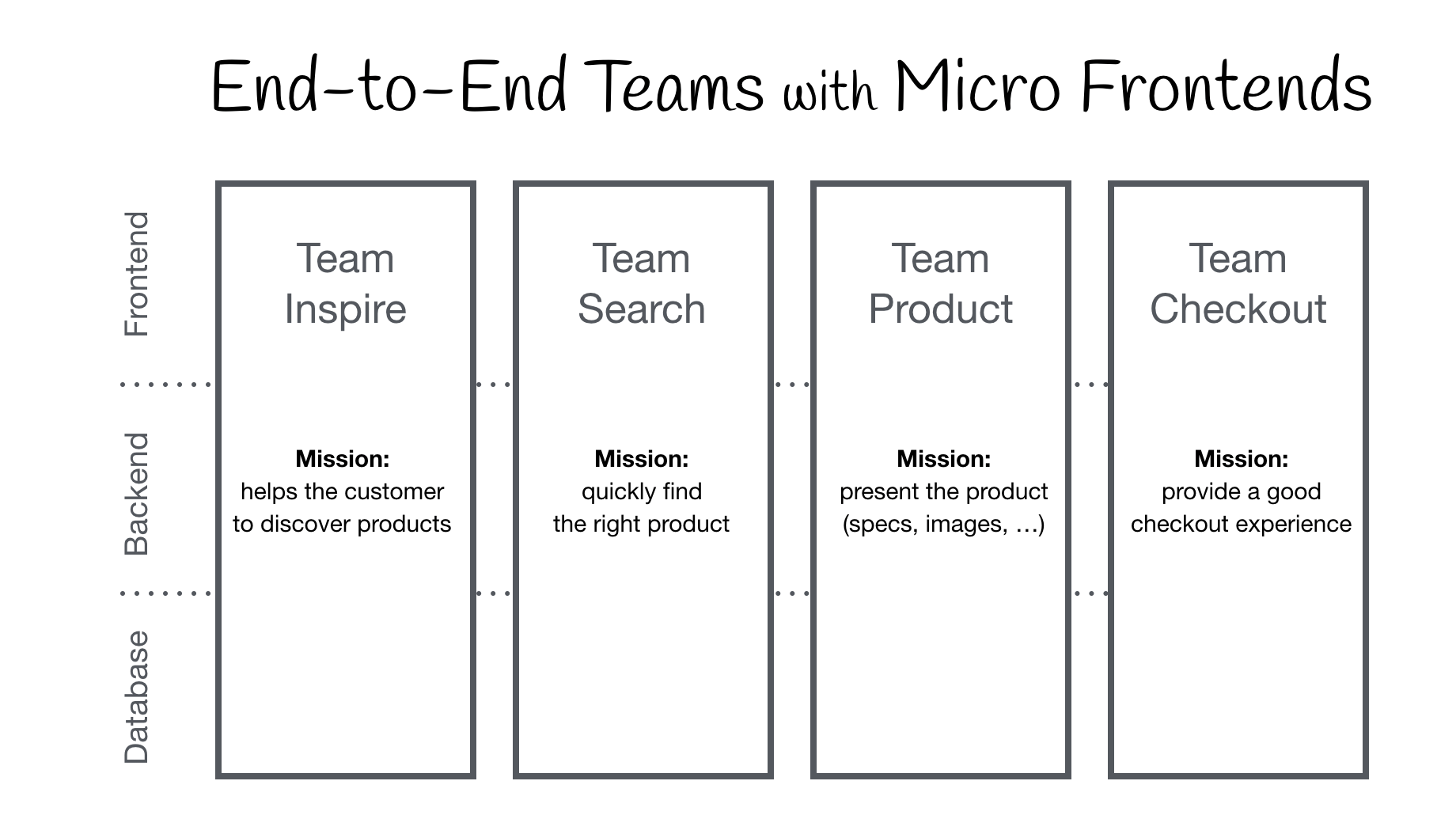

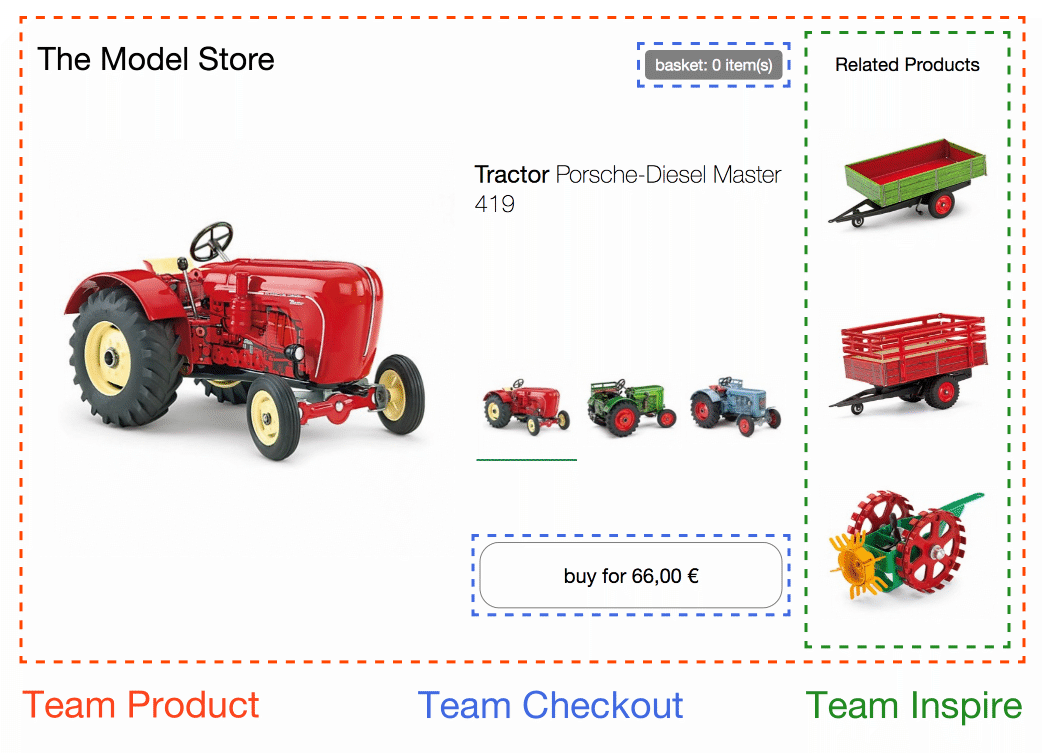

The idea behind Micro Frontends is to think about a website or web app as a composition of features which are owned by independent teams. Each team has a distinct area of business or mission it cares about and specialises in. A team is cross functional and develops its features end-to-end, from database to user interface.

However, this idea is not new. It has a lot in common with the Self-contained Systems concept. In the past approaches like this went by the name of Frontend Integration for Verticalised Systems. But Micro Frontends is clearly a more friendly and less bulky term.

Core Ideas behind Micro Frontends

Be Technology Agnostic

Each team should be able to choose and upgrade their stack without having to coordinate with other teams. Custom Elements are a great way to hide implementation details while providing a neutral interface to others.

Isolate Team Code

Don’t share a runtime, even if all teams use the same framework. Build independent apps that are self contained. Don’t rely on shared state or global variables.

Establish Team Prefixes

Agree on naming conventions where isolation is not possible yet. Namespace CSS, Events, Local Storage and Cookies to avoid collisions and clarify ownership.

Favor Native Browser Features over Custom APIs

Use Browser Events for communication instead of building a global PubSub system. If you really have to build a cross team API, try keeping it as simple as possible.

Build a Resilient Site

Your feature should be useful, even if JavaScript failed or hasn’t executed yet. Use Universal Rendering and Progressive Enhancement to improve perceived performance.

The Downside of Micro Frontends

There are several reasons why you might not want to use Micro Frontends.

-

__Failure or Downtime__. Unlike Micro Services (backend architecture), when a service is down the entire system might still be useful to the user. But with Micro Frontend this is a little bit tricky because if a particular micro fronted app is down it might lead to an incomplete page or might take down an entire section of the application, which can lead to bad user experience or simply render the application useless for the user.

-

__Managing Team Communication__ Communication between individual teams can be a hassle. Making sure each team meets the exact specification and also making sure that there is no code duplication between teams can be time consuming

-

__Testing Process__ Although each team can have their individual unit testing, implementing a comprehensive end to end (E2E) testing for the entire application can be challenging.

-

__Individual Size of Micro Frontend__ Depending on the different technology and the complexity of the features in each Micro Frontend, the application payload or size might be huge and the user may notice some lags while the application loads or while navigating between routes.

-

__Expensive to Implement__ Setting up a Micro Frontend architecture can be quite expensive to implement. You might end up paying a lot more to set up network infrastructure to hold all the Micro Frontends, and having to do so for each time-zone.

Module Federation

A scalable solution to sharing code between independent applications has never been convenient, and near impossible at scale. The closest we had was externals or DLLPlugin, forcing centralized dependency on a external file. It was a hassle to share code, the separate applications were not truly standalone and usually, a limited number of dependencies are shared. Moreover, sharing actual feature code or components between separately bundled applications is unfeasible, unproductive, and unprofitable.

We need a scalable solution to sharing node modules and feature/application code. It needs to happen at runtime in order to be adaptive and dynamic. Externals doesn’t do an efficient or flexible job. Import maps do not solve scale problems. I’m not trying to download code and share dependencies alone, I need an orchestration layer that dynamically shares modules at runtime, with fallbacks.

Module Federation is a type of JavaScript architecture Zack Jackson invented and prototyped. Then with the help of co-creator and the founder of Webpack — it was turned into one of the most exciting features in the Webpack 5 core (there’s some cool stuff in there, and the new API is really powerful and clean).

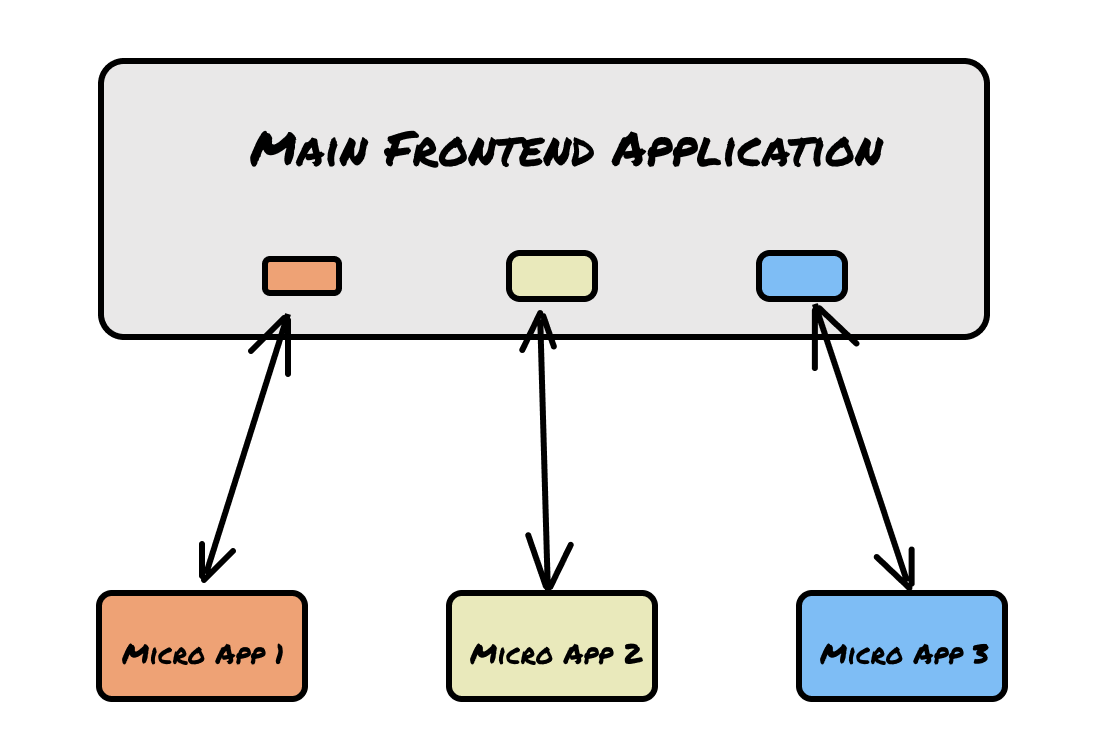

Module Federation allows a JavaScript application to dynamically load code from another application and in the process, share dependencies.

If an application consuming a federated module does not have a dependency needed by the federated code, Webpack will download the missing dependency from that federated build origin.

Code is shared if it can be, but fallbacks exist in each case. Federated code can always load its dependencies but will attempt to use the consumers’ dependencies before downloading more payload. This means less code duplication and dependency sharing just like a monolithic Webpack build.

Terminology

- Module federation: the same idea as Apollo GraphQL federation — but applied to JavaScript modules. In the browser and in node.js. Universal Module Federation

- A host: a Webpack build that is **initialized first during a page load **(when the onLoad event is triggered)

- A remote: another Webpack build, where part of it is being consumed by a “host”

- Bidirectional-hosts: when a bundle or Webpack build can work as a host or as a remote. Either consuming other applications or being consumed by others — at runtime

It’s important to note that this system is designed so that each completely standalone build/app can be in its own repository, deployed independently, and run as its own independent SPA.

These applications are all bi-directional hosts. Any application that’s loaded first, becomes a host. As you change routes and move through an application, it loads federated modules in the same way you would implement dynamic imports. However if you were to refresh the page, whatever application first starts on that load, becomes a host.

Let’s say each page of a website is deployed and compiled independently. I want this micro-frontend style architecture but do not want page reloads when changing route. I also want to dynamically share code & vendors between them so it’s just as efficient as if it was one large Webpack build, with code splitting.

Landing on the home page app would make the “home” page the “host”. If you browse to an “about” page, the host (home page spa) is actually dynamically importing a module from another independent application (the about page spa). It doesn’t load the main entry point and another entire application: only a few kilobytes of code. If I am on the “about” page and refresh the browser. The “about” page becomes the “host” and browsing back to the home page again would be a case of the about page “host” Fetching a fragment of runtime from a “remote” — the home page. All applications are both remote and host, consumable and consumers of any other federated module in the system.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Last update on 25 Mar 2022

---